- "John Murdoch was a General in the Civil War."

Murdoch never served in the military in any capacity.

- "Farm property was acquired by General John Murdoch in 1778 when the large Spanish colonial grants were being broken up."

Murdoch wasn't born until 1814, and he didn't move to St. Louis until 1838.

- "John Murdoch named his farm Shrewsbury Park after a place of the same name in England."

Murdoch's property was called Murdoch Farm. Farrar & Tate, who developed the land in the 1890's long after Murdoch's death, named it Shrewsbury Park after a town in England.

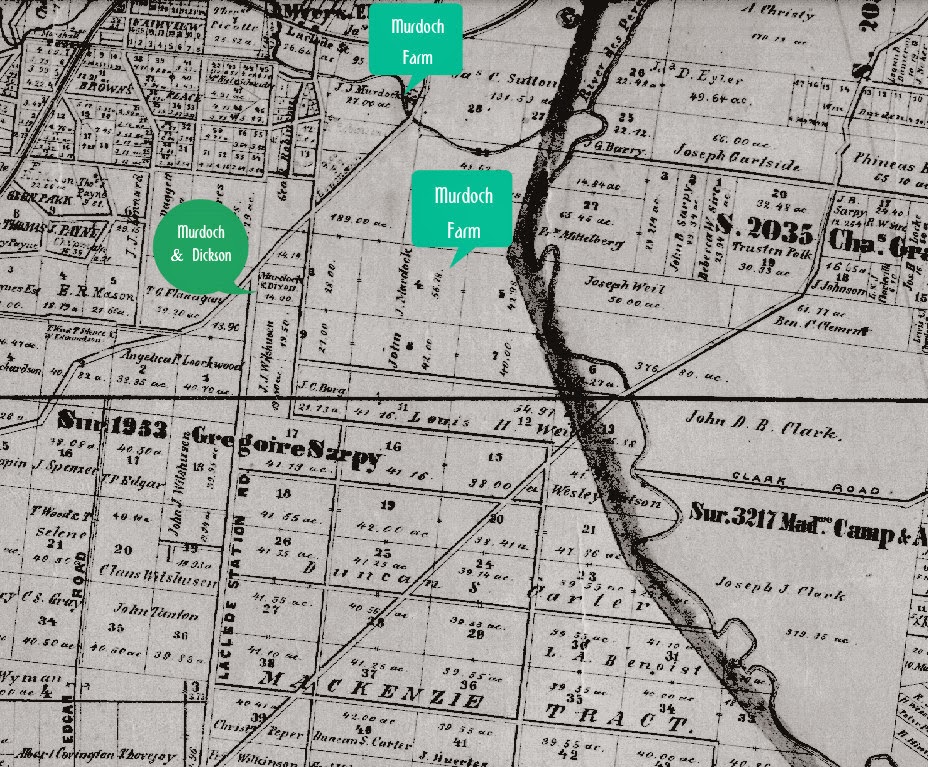

- "By 1890 Gregorie Sarpy's land was divided into farms. One of these farms was owned by John Murdoch."

Murdoch bought his farm land in the 1850's, and there were other farmers in the area at that time. He died in 1880.

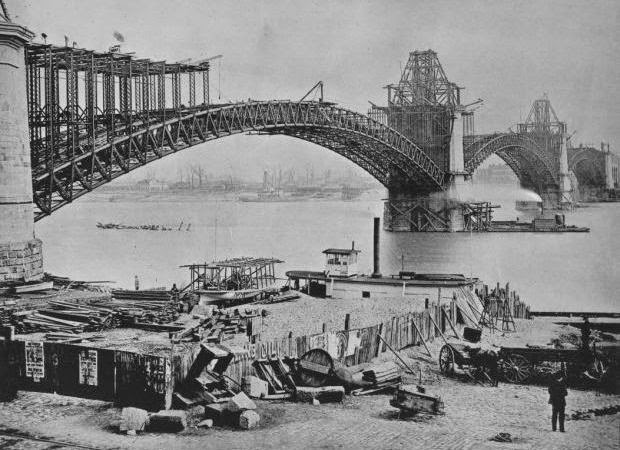

At first glance, it might not seem as though John Murdoch left much of a legacy behind after he died, especially since it appears that he had no surviving heirs. But I would beg to differ. It is pretty remarkable that a twenty-four year old man would leave his mom, dad, and siblings behind to travel nearly 1,000 miles to a place that was still pretty much a frontier town. Yet that is what John Murdoch did in 1838. He developed the successful firm of Murdoch & Dickson, expanded into other business endeavors with his partner, Charles K. Dickson, and built a life that included marrying Dickson's niece and starting a family. The two families were so close in life that in death they are all buried in the same plot. Many parts of St. Louis history were touched by the two men, including subdivisions, banks, insurance companies, railroads, Eads Bridge, and the Mercantile Library.

When he established Murdoch Farm in "the country" following his marriage in 1855, he must have felt like he was living the American dream. For the first time, he owned a home and the surrounding land (lots of it). The farm was a microcosm of America at the time, with servants and slaves to keep the farm functional. And yet Murdoch freed his slaves before the Civil War ended, and set them up with land and the means to sustain it.

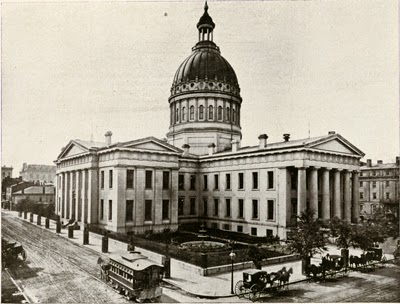

But as sometimes happens, Murdoch's dream turned into a nightmare. Whether through poor management, bad real estate investments, a declining economy - or maybe a combination of all those things - John Murdoch forfeited the business when his friend and partner, Charles Dickson, died. And then he lost his home and farm, literally on the court house steps. For all intents and purposes, he was destitute when he died in 1880, leaving his wife Julia to continue raising their six children on her own.

Murdoch Farm, however, took on a life of its own. The property which once provided solace to a single family began to offer city dwellers an opportunity to live in a country environment filled with fresh, clean air, quiet streets, local dairy products and produce. It presented a sanctuary for German immigrants seeking a place to worship in their native tongue. A building once home to the sounds of the Murdoch family was occupied with voices raised in prayer. From its start as Shrewsbury Park in the late 1890s, home to a few dozen families, the community of Shrewsbury is now filled with many churches, schools, businesses and over 6,000 residents. John Murdoch, as a businessman engaged in many real estate transactions, would be impressed with the development that has occurred on the land he once cultivated. There may no longer be any crops, but a strong sense of community has grown in the area.

I'll leave you with the poem written about Shrewsbury Park in 1890. I think John Murdoch would have appreciated the sentiment.

|

| Shrewsbury Poem |